creating equity in a company that eventually will become publicly traded or acquired, generating a multi-million-dollar payoff.

Scalable startups require risk capital to fund their search for a business model, and they attract investment from equally crazy financial investors—venture capitalists. They hire the best and the brightest. Their job is to search for a repeatable and scalable business model. When they find it, their focus on scale requires even more venture capital to fuel rapid expansion.

Scalable startups tend to group together in innovation clusters (Silicon Valley, Shanghai, New York, Boston, Israel, etc.). They make up a small percentage of the six types of startups, but because of the outsize returns, attract all the risk capital (and press).

Just in the last few years we’ve come to see that we had been building scalable startups inefficiently. Investors (and educators) treated startups as smaller versions of large companies. We now understand that’s just not true. While large companies execute known business models, startups are temporary organizations designed to search for a scalable and repeatable business model.

This insight has begun to change how we teach entrepreneurship, incubate startups and fund them.

|

Buyable Startups: Born to Flip

In the last five years, Web and mobile app startups that are founded to be sold to larger companies have become popular. The plummeting cost required to build a product, the radically reduced time to bring a product to market and the availability of angel capital willing to invest less than a traditional VCs—$100K to $1M versus $4M on up—has allowed these companies to proliferate, and their investors to make money. Their goal is not to build a billion dollar business, but to be sold to a larger company for $5-$50M.

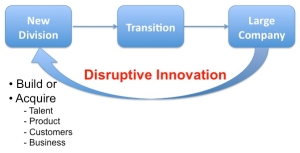

Large Company Startups: Innovate or Evaporate

Large companies have finite life cycles. And over the last decade those cycles have grown shorter. Most grow through sustaining innovation, offering new products that are variants around their core products. Changes in customer tastes, new technologies, legislation, new competitors, etc. can create pressure for more disruptive innovation—requiring large companies to create entirely new products sold to new customers in new markets (i.e. Google and Android). Existing companies do this by either acquiring innovative companies (see Buyable Startups above) or attempting to build a disruptive product internally. Ironically, large company size and culture make disruptive innovation extremely difficult to execute.

|

Social Startups: Driven to Make a Difference

Social entrepreneurs are no less ambitious, passionate, or driven to make an impact than any other type of founder. But unlike scalable startups, their goal is to make the world a better place, not to take market share or to create to wealth for the founders. They may be organized as a nonprofit, a for-profit, or hybrid.

So What?

When I read policy papers by government organizations trying to replicate the lessons from the valley, I’m struck how they seem to miss some basic lessons.

- Each of these six very different startups requires very different ecosystems, unique educational tools, economic incentives (tax breaks, paperwork/regulation reduction, incentives), incubators and risk capital.

- Regions building a cluster around scalable startups fail to understand that a government agency simply giving money to entrepreneurs who want it is an exercise in failure. It is not a “jobs program” for the local populace. Any attempt to make it so dooms it to failure.

- A scalable startup ecosystems is the ultimate capitalist exercise. It is not an exercise in “fairness” or patronage. While it’s a meritocracy, it takes equal parts of risk, greed, vision and obscene financial returns. And those can only thrive in a regional or national culture that supports an equal mix of all those.

- Building an scalable startup innovation cluster requires an ecosystem of private not government-run incubators and venture capital firms, outward-facing universities, and a rigorous startup selection process.

- Any government that starts public financing entrepreneurship better have a plan to get out of it by building a private VC industry. If they’re still publically funding startups after five to ten years they’ve failed.

To date, Israel is only country that has engineered a successful entrepreneurship cluster from the ground up. It’s Yozma program kick-started a private venture capital industry with government funds (emulating the U.S. lesson of using SBIC funds), but then the government got out of the way.

In addition, the Israeli government originally funded 23 early stage incubators but turned them over to the VCs to own and manage. They’re run by business professionals (not real-estate managers looking to rent out excess office space) and entry is not for life-style entrepreneurs, but is a bootcamp for VC funding.

Unless the people who actually make policy understand the difference between the types of startups and the ecosystem necessary to support their growth, the chance that any government policies will have a substantive effect on innovation, jobs or the gross domestic product is low.