I ran into Ricardo Dos Santos and his amazing Qualcomm Venture Fest a few years ago and was astonished with its breath and depth. From that day on, when I got asked about which corporate innovation program had the best process for idea selection, I started my list with Qualcomm.

This is part 2 of Ricardo’s “post mortem” of the life and death of Qualcomm’s corporate entrepreneurship program. Part 1 outlining the program is here. Read it first.

———

What Qualcomm corporate innovation challenges remained?

Ironically, our very success in creating radically new product and business ideas ran headlong into cultural and structural issues as well as our entrenched R&D driven innovation model:

- Cultural Issues: Managers approved their employees sign-up for the bootcamp, but became concerned with the open-ended decision timelines that followed for most of the radical ideas. Employees had a different concern – they simply wanted more clarity on how to continue to be involved, since formal rules of engagement ended with the bootcamp.

- Structural Issues: Most of the radical ideas coming out of the 3-month bootcamp possessed a high hypotheses-to-facts ratio. When the teams exited the bootcamp, however, it was unclear which existing business unit should evaluate them. Since there weren’t corporate resource for further evaluation, (one of our programs’ constraints was not to create new permanent infrastructures for implementation,) we had no choice but to assign the idea to a business unit and ask them to perform due diligence the best they could. (By definition, before they had a chance to fully buy into the idea and the team).

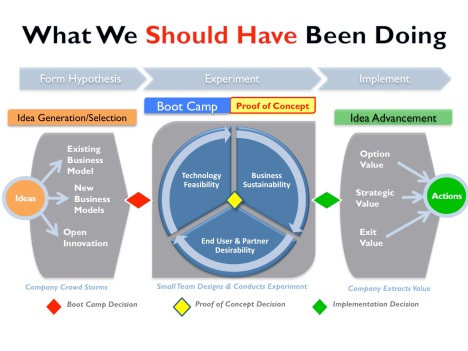

With hindsight we should have had “proof of concepts” tested in a corporate center (think ‘pop-up incubator’) where they would do extensive Customer Discovery. We should had done this before assigning the teams to a particular business unit (or had the ability to create a new business unit, or spin the team out of the company).

The last year of the program, we tried to solve this problem by requiring that the top 20 teams first seek a business unit sponsor before being admitted into the bootcamp (and we raised a $5 million fund from the BUs earmarked for initial implementation ($250K/team.) Ironically this drew criticism from some execs fearing we might have missed the more radical, out-of-the box ideas!

- Entrenched Innovation Model Issues: Qualcomm’s existing innovation model – wireless products were created in the R&D lab and then handed over to existing business units for commercialization – was wildly successful in the existing wireless and mobile space. Venture Fest was not integral to their success. Venture Fest was about proposing new ventures, sometimes outside the wireless realm, by stressing new business models, design and open innovation thinking, not proposing new R&D projects.These non-technical ideas ran counter to the company’s existing R&D, lab-to-market model that built on top of our internally generated intellectual property. The result was that we couldn’t find internal homes for what would have been great projects or spinouts. (Eventually Qualcomm did create a corporate incubator to handle projects beyond the scope of traditional R&D, yet too early to hand-off to existing business unit).

We were asking the company’s R&D leads, the de-facto innovation leaders, who had an existing R&D process that served the company extremely well, to adopt our odd-ball projects. Doing so meant they would have to take risks for IP acquisition and customer/market risks outside their experience or comfort zone. So when we asked them to embrace these new product ideas, we ran into a wall of (justified) skepticism. Therefore a major error in setting up our corporate innovation program was our lack of understanding how disruptive it would be to the current innovation model and to the executives who ran the R&D Labs.

What could have been done differently?

We had relative success flowing a good portion of ideas from the bootcamp into the business and R&D units for full adoption, partial implementation or strategic learning purposes, but it was a turbulent affair. With hindsight, there were four strategic errors and several tactical ones:

1) We should have recruited high level executive champions for the program (besides the CEO). They could have helped us anticipate and solve organizational challenges and agree on how we planned to manage the risks.

2) We should have had buy-in about the value of disruptive new business models, design and open innovation thinking.

3) We unknowingly set up an organizational conflict on day one. We were prematurely pushing some of the teams in the business units. The ‘elephant in the room’ was that the Venture Fest program didn’t fit smoothly with the BU’s readiness for dealing with unexpected ‘bottoms up’ innovation, in a quarterly- centric, execution environment.

4) Our largest customer should have been the R&D units, but the reality was that we never sold them that the company could benefit by exploring multiple innovation models to reduce the risks of disruption – we had taken this for granted and met resistance we were unprepared to handle.

- The Venture Fest program truly was ground breaking. Yet we never told anyone outside the company about it. We should have been sharing what we built with the leading business press, highlighting the vision and support of the program’s originator, the CEO.

- We should have asked for a broader innovation time off and incentive policy for employees, managers, and executives. Entrepreneurial employees must have clear opportunities to continue to own ideas through any stage of funding – that’s the major incentive they seek. Managers and execs should be incentivized for accommodating employee involvement and funding valuable experiments.

- We needed a for a Proof of Concept center. Radical ideas seldom had an obvious home immediately following the bootcamp. We lacked a formal center that could help facilitate further experiments before determining an implementation path. A Proof of Concept center, which is not the same as a full-fledged incubator, would also be responsible to develop a companywide core competence in business model and open innovation design and a VC-like, staged-risk funding decision criteria for new market opportunities.

- It’s hard to get ideas outside of a company’s current business model get traction (given that the projects have to get buy-in from operating execs) – encouraging spin-offs is a tactic worth considering to keep the ideas flowing.

Epilogue

The program became large enough that it came time to choose between expanding the program or making it more technology focused and closely tied to corporate R&D. In the end my time in the sun eventually ran out.

I had the greatest learning experience of my life running Qualcomm’s corporate entrepreneurship program and met amazingly brave and gracious employees with whom I’ve made a lifetime connection. I earnestly believe that large corporations should emulate Lean Startups (Business model design, Customer Development and Agile Engineering.) I am now eager to share and discuss the insights with other practitioners of innovation – I can be reached at [email protected]

Lessons Learned

- We now have the tools to build successful corporate entrepreneurship programs.

- However, they need to match a top-level (board, CEO, exec staff) agreement on strategy and structure.

- If I were starting a corporate innovation program today, I’d use the Lean LaunchPad classes as the starting framework.

- Developing a program to generate new ideas is the easy part. It gets really tough when these projects are launched and have to fight for survival against current corporate business models.