In the last few years we’ve recognized that a startup is not a smaller version of a large company. We’re now learning that companies are not larger versions of startups.

There’s been lots written about how companies need to be more innovative, but very little on what stops them from doing so.

Companies looking to be innovative face a conundrum: Every policy and procedure that makes them efficient execution machines stifles innovation.

This first post will describe some of the structural problems companies have; follow-on posts will offer some solutions.

—-

Facing continuous disruption from globalization, China, the Internet, the diminished power of brands, a changing workforce, etc., existing enterprises are establishing corporate innovation groups. These groups are adapting or adopting the practices of startups and accelerators—disruption and innovation rather than direct competition, customer development versus more product features, agility and speed versus lowest cost.

But paradoxically, in spite of all their seemingly endless resources, innovation inside of an existing company is much harder than inside a startup. For most companies it feels like innovation can only happen by exception and heroic efforts, not by design. The question is—why?

The Enterprise: Business Model Execution

We know that a startup is a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model. The corollary for an enterprise is:

A company is a permanent organization designed to execute a repeatable and scalable business model.

Once you understand that existing companies are designed to execute then you can see why they have a hard time with continuous and disruptive innovation.

Every large company, whether it can articulate it or not, is executing a proven business model(s). A business model guides an organization to create and deliver products/service and make money from it. It describes the product/service, who is it for, what channel sells/deliver it, how demand is created, how does the company make money, etc.

Somewhere in the dim past of the company, it too was a startup searching for a business model. But now, as the business model is repeatable and scalable, most employees take the business model as a given, and instead focus on the execution of the model—what is it they are supposed to do every day when they come to work. They measure their success on metrics that reflect success in execution, and they reward execution.

It’s worth looking at the tools companies have to support successful execution and explain why these same execution policies and processes have become impediments and are antithetical to continuous innovation.

20th century Management Tools for Execution

In the 20th century business schools and consulting firms developed an amazing management stack to assist companies to execute. These tools brought clarity to corporate strategy, product line extension strategies, and made product management a repeatable process.

For example, the Boston Consulting Group 2 x 2 growth-share matrix was an easy to understand strategy tool—a market selection matrix for companies looking for growth opportunities.

Strategy Maps are a visualization tool to translate strategy into specific actions and objectives, and to measure the progress of how the strategy gets implemented.

Product management tools like Stage-Gate® emerged to systematically manage Waterfall product development. The product management process assumes that product/market fit is known, and the products can get spec’d and then implemented in a linear fashion.

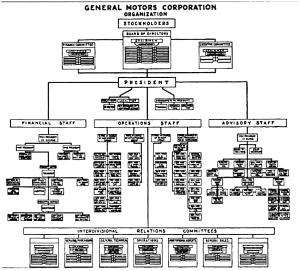

Strategy becomes visible in a company when you draw the structure to execute the strategy. The most visible symbol of execution is the organization chart. It represents where employees fit in an execution hierarchy; showing command and control hierarchies—who’s responsible, what they are responsible for, and who they manage below them, and report to above them.

All these tools – strategy, product management and organizational structures, have an underlying assumption: that the business model—which features customers want, who the customer is, what channel sells/delivers the product or service, how demand is created, how does the company make money, et.—is known, and that all the company needed is a systematic process for execution.

Driven by Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) and Processes

Once the business model is known, the company organizes around that goal and measures efforts to reach the goal, and seeks the most efficient ways to reach the goal. This systematic process of execution needs to be repeatable and scalable throughout a large organization by employees with a range of skills and competencies. Staff functions in finance, human resources, legal departments and business units developed Key Performance Indicators, processes, procedures and goals to measure, control and execute.

Paradoxically, these very KPIs and processes, which make companies efficient, are the root cause of corporations’ inability to be agile, responsive innovators.

This is a big idea.

Finance The goals for public companies are driven primarily by financial Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s). They include: return on net assets (RONA), return on capital deployed, internal rate of return (IRR),