Today the National Institutes of Health announced they are offering my Lean LaunchPad class (I-Corps @ NIH ) to commercialize Life Science.

There may come a day that one of these teams makes a drug, diagnostic or medical device that saves your life.

—-

Over the last two and a half years the National Science Foundation I-Corps has taught over 300 teams of scientists how to commercialize their technology and how to fail less, increasing their odds for commercial success.

After seeing the process work so well for scientists and engineers in the NSF, we hypothesized that we could increase productivity and stave the capital flight by helping Life Sciences startups build their companies more efficiently.

So last fall we taught 26 life science and health care teams at UCSF in therapeutics, diagnostics and medical devices. 110 researchers and clinicians, and Principal Investigators got out of the lab and hospital, and talked to 2,355 customers, tested 947 hypotheses and invalidated 423 of them. The class had 1,145 engagements with instructors and mentors.

The results from the UCSF Lean LaunchPad Life Science class showed us that the future of commercialization in Life Sciences is Lean—it’s fast, it works and it’s unlike anything else ever done. It’s going to get research from the lab to the bedside cheaper and faster.

Translational Medicine

In life sciences the process of moving commercializing research—moving it from the lab bench to the bedside—is called Translational Medicine.

The traditional model of how to turn scientific discovery into a business has been:

1) make a substantive discovery, 2) write a business plan/grant application, 3) raise funding, 4) execute the plan, 5) reap the financial reward.

For example, in therapeutics the implicit assumption has been that the primary focus of the venture was to validate the biological and clinical hypotheses (i.e. What buttons does this molecule push in target cells and what happens when these buttons are pushed? What biological pathways respond?) and then when these pathways are impacted, why do we believe it will matter to patients and physicians?

We assumed that for commercial hypotheses (clinical utility, who the customer is, data and quality of data, how reimbursement works, what parts of the product are valuable, roles of partners, etc.) if enough knowledge was gathered through proxies or research a positive outcome could be precomputed. And that with sufficient planning successful commercialization was simply an execution problem. This process built a false sense of certainty, in an environment that is fundamentally uncertain.

We now know the traditional translational medicine model of commercialization is wrong.

The reality is that as you validate the commercial hypotheses (i.e. clinical utility, customer, quality of data, reimbursement, what parts of the product are valuable, roles of CRO’s, and partners, etc.), you make substantive changes to one or more parts of your initial business model, and this new data affects your biological and clinical hypotheses.

We believe that a much more efficient commercialization process recognizes that 1) there needs to be a separate, parallel path to validate the commercial hypotheses and 2) the answers to the key commercialization questions are outside the lab and cannot be done by proxies. The key members of the team—CEO, CTO, principal investigator—need to be actively engaged talking to customers, partners, regulators, etc.

And that’s just what we’re doing at the National Institutes of Health.

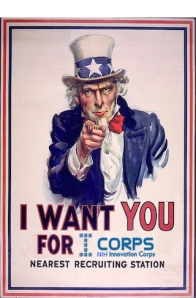

Join the I-Corps @ NIH

Today the National Institutes of Health announced the I-Corps at NIH.

It’s a collaboration with the National Science Foundation (NSF) to develop NIH-specific version of the Innovation-Corps. (Having these two federal research organizations working together is in itself a big deal.) We’re taking the class we taught at UCSF and creating an even better version for the NIH. (I’ll open source the syllabus and teaching guide later this year.)

The National Cancer Institute SBIR Development Center, is leading the pilot, with participation from the SBIR & STTR Programs at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

The class provides real world, hands-on learning on how to reduce commercialization risk in early stage therapeutics, diagnostics and device ventures. We do this by helping teams rapidly:

The class provides real world, hands-on learning on how to reduce commercialization risk in early stage therapeutics, diagnostics and device ventures. We do this by helping teams rapidly:

- define clinical utility now, before spending millions of dollars

- understand the core customers and the sales and marketing process required for initial clinical sales and downstream commercialization

- assess intellectual property and regulatory risk before they design and build

- gather data essential to customer partnerships/collaboration/purchases before doing the science

- identify financing vehicles before you need them.

Like my Stanford/Berkeley and NSF classes, the I-Corps @ NIH is a nine-week course. It’s open to NIH SBIR/STTR Phase 1 grantees.

The class is team based. To participate grantees assemble three-member teams that include:

- C-Level Corporate Officer: A high-level company executive with decision-making authority;

- Industry Expert: An individual with a prior business development background in the target industry; and

- Program Director/Principal Investigator (PD/PI): The assigned PD/PI on the SBIR/STTR Phase I award.

Space is limited to 25 of the best teams with NIH Phase 1 grants. Application are due by August 7th (details are here.)

If you’re attending the BIO Conference join our teaching team (me, Karl Handeslman, Todd Morrill and Alan May) at the NIH Booth Wednesday June 25th at 2:00 pm for more details. Or sign up for the webinar on July 2nd here.

—

This class takes a village: Michael Weingarten and Andrew Kurtz at the NIH, the teaching team: Karl Handeslman, Todd Morrill and Alan May, Babu DasGupat and Don Millard at the NSF, Erik Lium and Stephanie Marrus at UCSF, Jerry Engel and Abhas Gupta, Errol Arkilic at M34 Capital and our secret supporters; Congressman Dan Lipinski and Tom Kalil and Doug Rand at the OSTP and tons more.

Lessons Learned

- There needs to be a separate, parallel path to validate the commercial hypotheses

- The answers to commercialization questions are outside the lab

- They cannot be done by proxies

- Commercial validation affects biological and clinical hypotheses.

This post originally appeared on Steve Blank’s blog and is republished by permission.