Two of the hot topics in education in the last few years have been Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC’s) and the flipped classroom. I’ve been experimenting with both of them.

What I’ve learned (besides being able to use the word “pedagogy” in a sentence) is 1) assigning students lectures as homework doesn’t guarantee the students will watch them and 2) in a flipped classroom you can become hostage to the pedagogy.

Here’s the story of what we tried and what we learned.

MOOCs—Massive Open Online Courses

A MOOC is a complicated name for a simple idea—an online course accessible to everyone over the web. I created my MOOC by serendipity. Learning how to optimize it in my classes has been a more deliberate and iterative process.

When my Lean LaunchPad class was adopted by the National Science Foundation, we taught our original classes to scientists scattered across the U.S. We adopted WebEx, a web video conferencing tool, to hold our classes remotely. Just like my students at Stanford, these NSF teams got out of the building and spoke to 10-15 customers a week. Back in their weekly class, the scientists would present their results in front of their peers—in this case via Webex, as the teaching team gave them critiques and “guidance”. When their presentations were over, it was my turn. I lectured to these remote students about the next week’s objectives.

Is it Live or Is It a MOOC?

After the first NSF class held via videoconference, it dawned on me that since I wasn’t physically in front of the students, they wouldn’t know if my lecture was live or recorded.

Embracing the “too dumb to know it can’t be done,” I worked with a friend from Stanford, Sebastian Thrun and his startup Udacity, to put my Lean LaunchPad lectures online. Rather than just have me drone on as a talking head, I hired an animator to help make the lectures interesting, and the Udacity team had the insight to suggest I break up my lecture material into small, 2-4 minute segments that matched students’ attention spans.

Over a few months we developed the online lectures, then tried it as a stand-in for me on the NSF videoconferences, and found that because of the animations and graphics the students were more engaged than if I were teaching it in person. Ouch.

Now the NSF teams were learning from these online lectures instead of video conferenced lectures—but the online lectures were still being played during class time.

I wondered if we could be more efficient with our classroom time.

Flipping

Back at Stanford and Berkeley, I realized that I could use my newly created Lean LaunchPad MOOC and “flip” the classroom. It sounded easy, I had read the theory:

1) A flipped classroom moves lectures traditionally taught in class, and assigns them as homework. Therefore my students will all eagerly watch the videos and come to class ready to apply their knowledge.

2) This would eliminate the need for any lecture time in class. And as a wonderful consequence,

3) I could now admit more teams to the class because we’d now have more time for teams to present.

So much for theory. I was wrong on all three counts.

Theory Versus Practice

After each class, we’d survey the students and combine it with a detailed instructor post-mortem of lessons learned. (An example from our UCSF Lean LaunchPad for Life Sciences Class is here.)

Here’s what we found when we flipped the classroom:

- More than half the students weren’t watching the lectures at home.

- Without an automated tool to take an attendance, I had no idea who was or wasn’t watching.

- Without lectures, my teaching team and I felt like observers. Although we were commenting and critiquing on students presentations, the flipped classroom meant we were no longer in the front of the room.

- No lectures meant no flexibility to cover advanced topics or real time ideas past the MOOC lecture material.

We decided we needed to fix these issues, one at a time.

- In subsequent classes we reduced class size from 10 teams to eight. This freed up time to get lecture and teaching time back in the classroom.

- We manually took attendance of who watched our MOOC (later this year this will be an automated part of the LaunchPad Central software we use to manage the classes).

- To get the teaching team front and center, I required students to submit questions about material covered in the MOOC lecture they watched the previous evening. I selected the best questions and used them to open the class with a discussion. I cold-called on students to ensure they all had understood the material.

- We developed advanced lectures which combined a summary of the MOOC material with new material such as lectures focused on domain specific perspectives. For example, in our UCSF Life Sciences class the four VCs who taught the class with me developed advanced business model lectures for therapeutics, diagnostics, medical devices and digital health. (These advanced lectures are now on-line and available to everyone who teaches the class.)

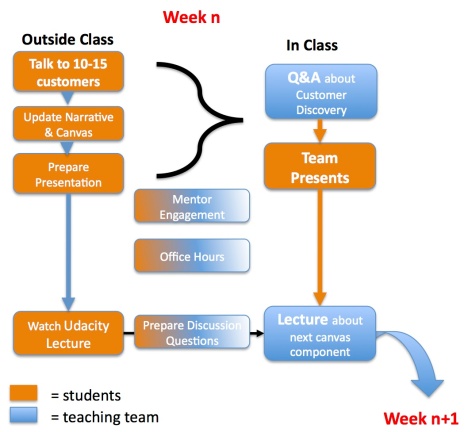

The class, now taught as hybrid flipped classroom, looks like this:

There’s still more to do.

- While we use LaunchPad Central to have the teams provide feedback to each other, knowledge sharing across the teams still needs to be deeper and more robust.

- While we try to give students tutorials for how to do Customer Discovery we need a better way to integrate these into the short time in quarter/semester.

- While we insist that an MVP is part of the class, we need a more rigorous process for building the MVP in parallel with Customer Discovery

Outcomes

Besides finding the right balance in a flipped classroom, a few other good things have come from these experiments. The Udacity lectures now have over 250,000 students. They are not only used in my classes but are also part of other educators’ classes, as well as being viewed by aspiring entrepreneurs as stand-alone tutorials.

My experiments in how to teach the Lean LaunchPad class have led to a 2 ½ day class for 75 educators per quarter (information here.) And we’ve found a pretty remarkable way to use the Lean LaunchPad to organize corporate innovation/incubator groups. (We opened source our teaching guide we use in the classes here.)

Lessons Learned

- Creating engaging MOOCs is hard

- Confirming that students watched the MOOCs is even harder

- The flipped classroom needs to be balanced with:

- Student accountability

- Instructor time in front of the class

- Advanced lectures